Clara Schumann – "surely you mean Robert?". This was the reaction last September 2019, when the bicentenary of the birth of Clara Wieck Schumann elicited a revival of her piano music and other works, and a spate of new recordings.

Although many a music listener will have heard of the legendary abbess Hildegard von Bingen, a gifted composer of church music around 1100 A.D., women composers from then until the 20th Century seem to have fallen into a "black hole" of obscurity.

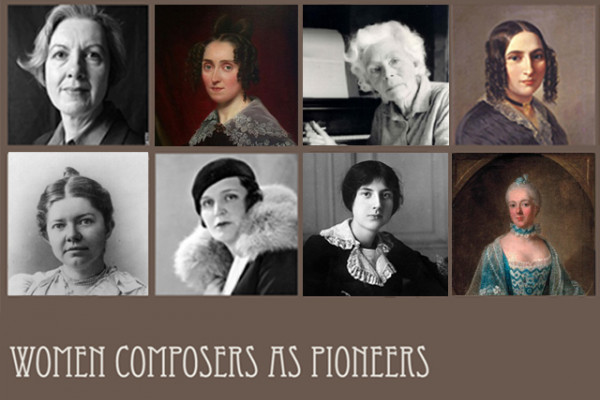

Christine ten Bokum, our speaker, will acquaint us with equally talented composers and highlight the circumstances of this glaring lack of recognition. We will encounter Belle van Zuylen, Louise Ferranc, Fanny Mendelssohn, Alma Mahler (or did I mean Gustav?), Lili Boulanger, Amy Beach, Cecile Chaminade, Germaine Tailleferre, Elisabeth Maconchy, Judith Weir and Sofia Gubaidulina … not forgetting the pioneering achievements of Clara Schumann herself. The big question – is male hegemony still in sway today?

Christine ten Bokum grew up in Zimbabwe, where she obtained her Licentiates in Piano Teaching. After moving to Holland with her young family, she pursued further studies in piano and harpsichord. She subsequently performed with the Telemann Ensemble, a baroque group, accompanied adult and children's church choirs, and taught piano privately.

After relocating to Brussels with her husband, she resumed piano teaching, playing in chamber music ensembles and accompanying singing students and examination candidates.

She hosts twice-yearly Associated Board examination sessions at her studio in Tervuren, and a monthly Music Appreciation group for members of WIC

Note: Content and images not intended for copyright infringement.